by Joanne M. Pierce

For the Catholic Church and many other Christian denominations, the Sunday before Easter marks the beginning of the most important week of the year – “Holy Week,” when Christians reflect on central mysteries of their faith: Christ’s Last Supper, crucifixion and resurrection from the dead.

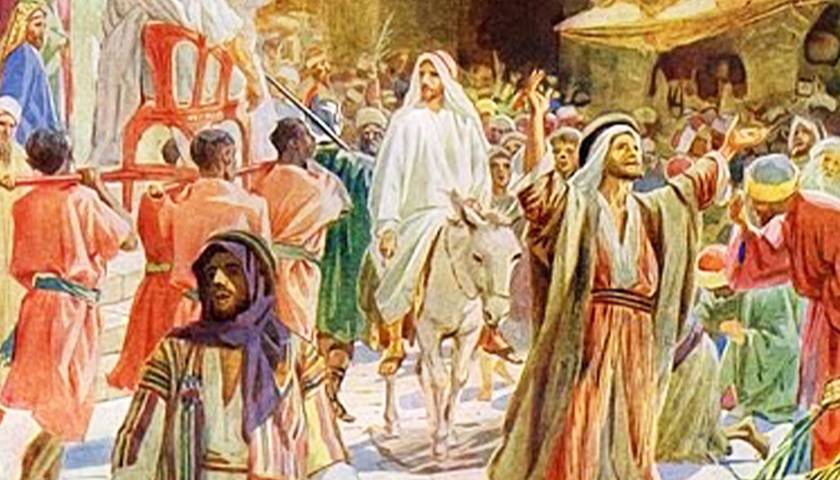

Palm Sunday commemorates the story of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem shortly before the Jewish holiday of Passover. According to the Christian Gospels, people lined the streets to greet him, waving palm branches and shouting words of praise.

As a specialist in Catholic liturgy and ritual, I think it’s clear that the deeper meaning of this Sunday is rooted in humility, rather than worldly veneration.

Humble service to others is a theme that runs through the New Testament. As the apostle Paul stressed, Christians believe that Jesus, the son of a carpenter, was also the son of God, who “emptied himself” of his divinity to become fully human. Jesus’ teachings in the Gospels praise “the meek, for they will inherit the earth,” and he proclaims that “whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant.”

Modern Catholic teachings describe humility as grounded in an understanding of one’s true relationship with God, one’s own gifts, and an openness to appreciating the talents of others.

Double symbols

Each of the four Gospels, the biblical books about Jesus’ life, describe him entering Jerusalem to prepare to celebrate Passover days before being betrayed, arrested, tried and sentenced to a criminal’s death by crucifixion. Each one explicitly says that he rode into the city on a donkey or a colt. Throughout the Bible, however, the word meaning “colt” is used almost exclusively for young donkeys, not horses.

This image brings to mind a line from the Book of Zechariah in the Jewish scriptures: The prophet describes a victorious king who enters Jerusalem “lowly and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.”

In Judaism, this passage from Zechariah is taken to refer to the Messiah, a spiritual king who would peacefully redeem Israel. The donkey itself is also interpreted as a sign of humility.

In Christianity, this animal becomes almost a symbol of Christ himself, given how it patiently suffers and bears others’ burdens. Horses, on the other hand, tend to be associated with royalty, power and war.

On the other hand, the palm branch had been associated with triumph and victory for hundreds of years before Christ. Winners of athletic contests, victorious generals and triumphant kings would be awarded or welcomed with waving palm branches, a sign of jubilation.

These Gospel narratives left Christians throughout the centuries with two important images for Palm Sunday, the procession with palm branches and the donkey: one associated with triumphant victory, and the other with quiet humility.

Historical development

The earliest evidence for a Palm Sunday procession comes from a late fourth-century religious woman named Egeria, who recorded her experiences on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land for her community in Spain.

While in Jerusalem, she describes assembly for prayer on the Mount of Olives in the early afternoon of Palm Sunday. This is a significant location just outside the city, where Christians believe that Jesus taught disciples, prayed in the garden of Gethsemane at its base, and ascended into heaven.

Afterward, the group processed down to the Anastasis, the church in Jerusalem marking the place believed to be Jesus’ tomb, for evening prayer. Among the crowd were children waving palms and olive branches.

Medieval Christian worship books from the 10th and 11th centuries show that a ritual procession outside churches became a standard feature of Palm Sunday celebrations in Western Christianity. In many parts of Europe, other spring flowers or budding branches might be used alongside palm or olive branches, and the Sunday could also be referred to as Flower or Willow Sunday.

Christ could be represented in the procession in numerous ways, such as the presence of the bishop or saints’ relics. In some areas, a carved figure of Christ seated on a donkey, called a Palmesel or “palm donkey,” could be pulled in front of the crowd.

During the mass after the procession, clergy would read a Gospel account of Christ’s crucifixion and death, traditionally from the Book of Matthew; today, Catholics use versions from other gospels as well. The reading would usually be chanted, with different voices taking the parts of the narrator, Christ, and other speakers, especially the crowd of people described as witnessing his trial, with the congregation still holding their palm branches.

Even today, in the contemporary Catholic calendar, the full title of this first Sunday of Holy Week is Palm Sunday of the Lord’s Passion.

Lasting symbols

Centuries of theological and artistic reflection have shaped today’s Catholic approach to Holy Week specifically, and to the concept of holiness in general.

The image of the quiet, patient, and unassuming donkey has communicated humility in art and in practice. No animals are mentioned in the descriptions of the birth of Jesus in the canonical gospels officially included in the Bible. However, other early Christian texts refer to a donkey at the manger or Mary seated on a donkey as she travels with Joseph. Medieval artists also depicted the nativity scene with both an ox and an ass in attendance, and Mary riding on a donkey.

The palm also came to be a wider symbol. Early saints who had died as martyrs – that is, who died rather than renounce their Christian faith – came to be pictured standing by a palm tree. More commonly, they were shown holding a palm branch, signifying their victory over death: Having given up their earthly lives to follow Christ, they were now united with him in Paradise. Martyrs are also frequently depicted with the instruments of their torture, helping worshippers to identify and venerate them.

All of these images are rooted in the narrative of Palm Sunday, with its image of Jesus, the carpenter’s son, riding on an ordinary donkey, yet acclaimed for a moment as though he were a worldly king. A similar paradox is at the heart of Christian teachings: that although Jesus Christ willingly died on a criminal’s cross, doing so was a victory over sin and death.

– – –

Joanne M. Pierce is a Professor Emerita of Religious Studies, College of the Holy Cross.

Photo “Entry into Jerusalem” by William Brassey Hole.

Appeared at and reprinted from theconversation.org

![]()