by Tom Raabe

The latest act in the clown show that is the Big Ten Conference’s postponement of football this fall occurred on Thursday afternoon when Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer green-lighted high school football in the state.

Twitter erupted into paroxysms of hope, and the Internet haruspices crouched down to read the chicken entrails. Might the decision of this control-freak governor, who a little more than a week earlier had expressed glee that the Big Ten was scrubbing football for the fall, augur a reversal of opinion among decision makers in the Upper Midwest and thus a possible revocation of the conference suspension of fall sports?

The league, for its part, did itself no favors on announcement day. The rollout of the postponement decision was as inept as the Obamacare website launch.

Had the poll numbers in her state turned, intimating that poll numbers in other Big Ten states had turned as well? Could the governor’s flip flop portend similar gymnastic feats in nearby states’ governor mansions, and concomitant 180s in conference presidents’ offices? Could conference schools be playing football … maybe even already next month?

Who knows? Every day — indeed, every couple of hours — there is a new, breathlessly reported development in the soap opera that is the Big Ten football postponement. Ohio State practiced in pads Tuesday! Jim Harbaugh told his Michigan team to be ready to play in October! A major voice in sports talk radio pegged the start date as October 10! Big Ten prexies were said to be revoting on Saturday! No, the vote’s slated for Monday! But no again, the Big Ten prexies have no immediate plans to meet, reliable sources say!

How did we get to this chaotic point? On August 5, the conference released a tentative football schedule. Everything pointed to the hallowed, historic Big Ten giving football the old college try. The fourteen conference schools would play conference games only; they would play ten of them; they would start in early September and conclude in mid-November, with two bye weeks built into every school’s schedule as a cushion against delays or virus outbreaks within teams or other disruptions. Coaches, players, and fans were optimistic; if cautious giddiness is a thing, they were that, too.

Coaches had assembled their teams; players were practicing; athletic departments were putting in place health protocols for fans and players. There was a hint of reluctance in the commissioner’s go signal, but most everyone, in their enthusiasm for football, burrowed past it and laid plans for some semblance of the grand old game on their campuses beginning in a month or so.

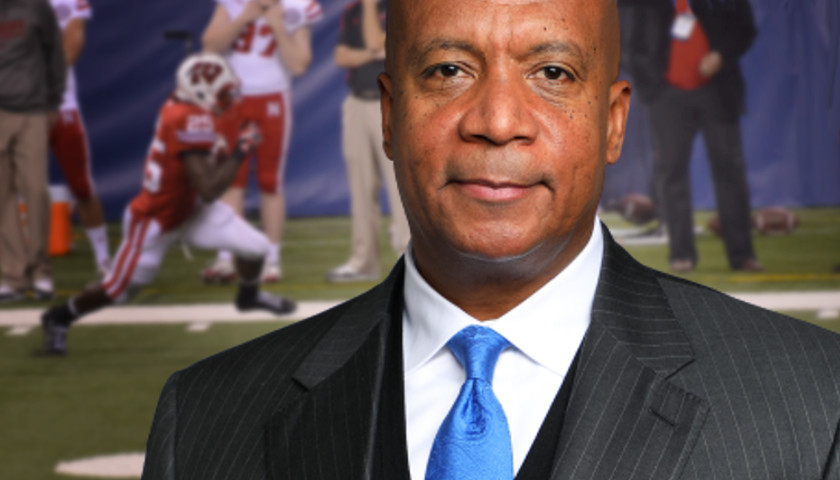

Six days later the commissioner of the Big Ten, Kevin Warren, blindsided them all by announcing that all fall sports — most prominently football — were canceled. This occurred on August 11, a full three weeks before the first scheduled game. There would be no delay in the decision, no waiting a week or two to see if virus conditions improved or how other major conferences were going to proceed. The issue would not be revisited. The decision was irrevocable. Big Ten football for fall 2020 was finis, caput, done.

The fit hit the shan almost immediately. When news of the postponement was about to break, the coach of one conference school, Nebraska, tried to forestall the decision with a desperate eleventh-hour press conference. Scott Frost’s players, he said, were safer in the controlled environment of the Nebraska football program than they were at home — they would receive more testing, and better health care, there than they would anywhere else in Lincoln, or even at their parents’ house. His school would also lose $80 to $120 million without football, and most of the other sports at Nebraska would be hurt. Intriguingly, Coach Frost also floated the idea that his team might go rogue and play games wherever they could find them.

The “ungrateful” Cornhusker was inundated with a tsunami of pushback from the established sports media. Pundits with blue-blood Big Ten backgrounds were outraged at the coach’s temerity to suggest going off the Big Ten grid. A Michigan alum and a Northwestern grad, respectively, both well-known TV personalities, seemed more upset at Nebraska wanting to play football outside the Big Ten than they were at the Big Ten for dropping football for the fall. Another commentator told Nebraska, a parvenu in this the hoity-toity-est of major conferences, to mount its John Deere and drive its “double duals” back to where it came from.

Now, understand something about the Big Ten. It bows to no one in haughtiness. Its true-blue fans seem more concerned about winning a conference championship than they do a national championship; the Rose Bowl game seems more important to these folks than the national title game. Indeed, recent additions Maryland and Rutgers (entered in 2014), and Nebraska (2011), and even Penn State (1990), are not, and probably never will be, accepted as coequals by the legacy members. Some in the Great Lakes State are still annoyed that Michigan State got into the conference, and that happened in 1950, although, to be honest, that sentiment might derive more from University of Michigan arrogance, a discrete but equally obnoxious prejudice, than from Big Ten condescension. So arrogant is the conference that it probably thought its stature and reputation among conferences would force other leagues to do likewise and postpone their football schedules.

True to form, the Pac-12 fell in line, canceling all sports (for the rest of the calendar year!) later the same day. But three major conferences decided conditions were safe enough to play football this fall, and currently the Southeastern Conference, the Atlantic Coast Conference, and the Big 12 are all teeing it up later this month.

The Nebraska coach was soon joined in dissent by other league coaches, and even players and their parents. On August 16, the league’s best player, Ohio State quarterback Justin Fields, started an online petition for playing football that had garnered 230,000 signatures a day later. Parents of players from various Big Ten schools organized groups in opposition to the forced postponement; some showed up at Big Ten offices attempting to confront the commissioner and urge a reconsideration. And of course, the social media raged.

The league, for its part, did itself no favors on announcement day. The rollout of the postponement decision was as inept as the Obamacare website launch. Warren could speak only in benign generalities, saying meetings with conference medical people convinced league officials of “too much uncertainty regarding potential medical risks to allow our student-athletes to compete this fall.” Later in the day, on the league’s own Big Ten Network, he reiterated that “uncertainty” time and again while offering logorrheic responses to questions from an interviewer imploring him for explanation rather than confronting him about the decision. After which, he pulled down upon himself a cone of silence.

Since that time we have learned the vote to postpone was 11 to 3, the three no votes, it is widely assumed, coming from Ohio State, Iowa, and Nebraska. Also, various ideas for alternative seasons have bounced around the media: a spring season; a winter season, possibly played in central locations, in the domed stadiums of Big Ten Land; a six-team mini-league with each team playing ten games, home and home, against each other; a season starting around Thanksgiving time; and lastly the October 10 start-up date.

The situation is, as they say, fluid, but, officially, as of now, no football is officially on the docket for winter, spring, or fall. The financial damage the postponement imposes on the league is substantial. A number of schools are expected to lose upwards of $100 million. Athletic department jobs will be axed and departments will institute hiring freezes. Sports will be cut. All sports other than men’s basketball are heavily dependent upon finances generated by football and will suffer from the postponement. And Big Ten die-hards will be forced to watch Big Ten Network “classics” for the remainder of the calendar year!

But that’s minimal compared to the damage postponement will wreak on the playing field. Truth be told, the Big Ten is decades removed from any sort of football dominance. In the last 50 years, that is, since 1970, conference members have won two full national championships and one split title. Between 1970 and 1995, for example, the latter date the termination point of the old Big Eight conference, the Big Eight won seven national championships and one split title to the Big Ten’s zero. And since 1995, the league boasts only a half-loaf championship by Michigan in 1997 and two titles by Ohio State, in 2002 and 2014. The SEC, meanwhile, the heavyweights who live rent-free in Big Ten fans’ heads, has ruled college football, scoring 11 national championships since the new century began, and eight straight between 2006 and 2012.

In the last decade or so, thanks to the supremacy of Ohio State, the conference has clawed its way to respectability, and the last few years could legitimately be considered the second-most-powerful league in college football. Michigan, Penn State, and Wisconsin regularly people the top 20, and the Buckeyes are a bona fide national title contender every year.

Postponing the fall football season while three of the other main conferences are playing is sure to widen that gap once again. In addition to the financial hit, recruitment will be crushed, as premier high school football players who want to devote their lives to football will gravitate toward schools in conferences that look for reasons to play football rather than conferences that look for reasons not to play football.

It will be a sad sight come middle to late October when coaches and players, not to mention college presidents, in Big Ten country are sitting in front of their TVs watching college football being played in all its pomp and glory in the huge stadiums of the South while their giant coliseums sit nearby empty and dark.

– – –

Tom Raabe is a writer and editor living in Tempe, Arizona.

Photo “Big Ten Commissioner Kevin Warren” by Big Ten and photo “Big Ten Football” by Steve Schar CC2.0.

Well, at least we know now that this was never about the safety of the players. It was virtue signaling, plain and simple…by a diversity hire to boot. The Back When is America’s laughingstock.