by Steve Miller

“I can’t begin to understand what ballot harvesting is,” Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, the former Republican House Speaker, said in an interview in the wake of a 2018 political upset in Orange County, California. Democrats had swept the congressional seats in one of California’s few Republican strongholds, largely due to a well-executed strategy of harvesting, or the collection and submission of ballots by someone other than the voter.

Three election cycles later, Republicans are still on the backfoot when it comes to the nation’s recent embrace of absentee, mail, and early voting. But what critics call “election month” looks likely to endure indefinitely after taking hold in pandemic-prompted voting procedures widely adopted in 2020, ostensibly as a health precaution to promote social distancing.

After President Trump’s defeat in 2020, Republican-led legislatures worked to turn back the emergency voting measures in many states, to mixed success, and – after an expected GOP wave fizzled in 2022 – the Republican Party has turned away from Trump’s vilification of absentee voting to essentially say, “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.”

“We don’t want to wait till the fourth quarter to start scoring touchdowns when you have four quarters to put points on the board,” Republican National Committee chairwoman Ronna McDaniel said last month in promoting the new strategy. “We have to change the culture among Republican voters.”

But a range of factors suggest that Republicans are a long way from implementing that change. This impression emerges from interviews with election veterans from both parties in a number of pivotal states; disclosures about the left’s prodigious fundraising for private assistance to local election offices; and Democrats’ reinvigorated focus on community organizing in dense urban areas. The latter is a tradition reaching back more than a century but exploited in recent cycles to overwhelm the GOP’s onetime edge in collecting absentee ballots from the elderly and members of the armed forces.

“The left is about 20 years ahead on getting these votes,” said Michael Bars, executive director of the conservative Election Transparency Initiative. “You can say it’s an absentee, get-out-the-vote model, an absentee ballot chase or ballot harvesting. But they’re ahead.”

And catching up isn’t easy, an RNC official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity in giving a grim assessment of a ground game still unfamiliar to the GOP.

“Strangers going door-to-door met with a ton of resistance from Republican voters,” the official said. He was referring to a strategy shift in 2016 when “the RNC changed its field structure to resemble the work that the Obama campaign did in 2008 and 2012 by focusing on training people to be organizers, to put together teams that were part of the community.” It turned out that, with Republicans tending to live in suburban developments, soliciting was frowned upon, and even prohibited, while the Democrats were, as ever, more welcome in urban settings, visiting apartment buildings, public libraries, and residential centers.

With even McDaniel still saying she doesn’t like absentee voting, not every Republican official is embracing the message.

“We promote in-person voting and we promote a message around in-person voting,” said Marci McCarthy, chairman of the DeKalb County (Georgia) Republican Party, in a jurisdiction that contains part of Atlanta and where President Biden won 83% of the vote in 2020. Nationally, 65% of the roughly 65 million absentee and mail-in voters said they voted for Biden in 2020.

The Golden State Lesson

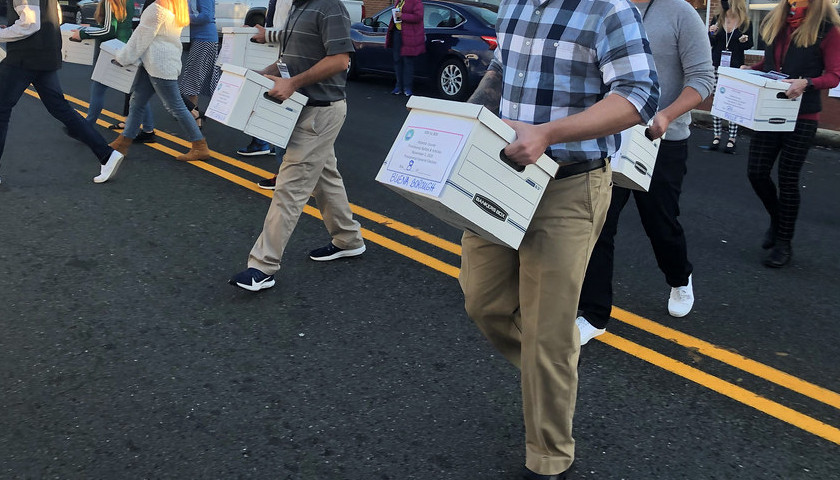

After enacting new voting rules in 2016 that allowed harvesting, California Democrats in the 2018 midterms dispatched volunteers and paid staffers to neighborhoods rich in registered Democrats who had received an absentee ballot but had not returned it. Some of the agents collected up to 200 ballots at a time and turned them in for counting.

Results were delayed as the ballots trickled in – a harbinger of today’s prolonged ballot counts as more states rely on mail voting. But the result was eventually clear: a GOP drubbing in Orange County.

“We got our asses handed to us,” said Jessica Millan Patterson, chair of California’s Republican Party, whose 2019 election to office was in part based on her vow to embrace harvesting for the party and avenge the Orange County defeat. “Democrats in California have normalized what would be considered voter fraud in the rest of the country. If I had my way, harvesting would be illegal, but we have to win more elections if we want to change laws.”

After taking over the party’s ground game, she coordinated each county party’s street teams, assembling paid staffers and volunteers to knock on doors of registered Republicans or those who have not registered but may be open to voting.

By 2020, local Republicans were holding “ballot parties” as part of campaign events, where people could hand over their ballots, specified in social media invitations as a “secure location, “ to be delivered to the election office.

The Opposition

Progressives defended their advantage. They followed their California triumph in 2018 with widespread ballot collection efforts in 2020’s presidential election and the 2022 midterms, where they largely thumped Republicans nationally, including holding the Senate despite widespread predictions that Republicans would sweep both houses of Congress.

Conservative critics contend that illegal harvesting was behind Democrat wins in Georgia and Arizona in 2020, although investigations failed to find illicit activity.

What they did find, though, was a well-oiled progressive machine with roots in community organizing, working with like-minded state administrations on ballot design, drop-box placement, and deploying lobbyists to push progressive voting strategies.

These are funded in part by $1 billion from nonprofits and individuals, the most influential of which is the Center for Technology and Civic Life, led by Tiana Epps-Johnson, a former fellow at the Obama Foundation who is joined at the center by staffers who learned their politics in progressive advocacy groups.

The voting strategy network is complemented by an impressive cadre of social media influencers. What was termed a “block by block street fight” by former Obama campaign manager David Plouffe in a 2020 book became a crusade for urban votes. Private funding distributed by the CTCL helped get-out-the-vote efforts in those areas by disproportionately allocating per-vote money to Democratic areas.

Ballot collectors go door-to-door in their targeted areas, working from a daily roadmap of “match backs,” or a list of voters who have received a mail ballot but have not yet cast it.

“In Washington, Republicans start each election at zero and Democrats at 90,” said Don Skillman, co-founder of Voter Science, a voter data group based in Bellevue, Washington. “Democrats know who donors and voters are and where they are. They have an eco-system with this non-profit outreach and know who they are talking to.”

Washington’s state Republican party did not respond to an interview request.

The New Order

The evolving hybrid voting procedures vary widely from state to state and, depending on the ways they came about, may or may not reflect the state autonomy envisioned in the U.S. Constitution’s stipulation that “the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.”

Ballot harvesting is explicitly illegal in Mississippi, while 11 other states have no law addressing the practice. Some states permit designated people, such as a relative or housemate, to turn in ballots, while 19 states allow a broader form of collection where voters can choose the person they want to act as their agent.

Republican lawmakers around the country have enacted numerous state and local laws since the pandemic-panicked 2020 national election in efforts to curb mail ballots and undo rules that allowed unpoliced mail ballot drop boxes, mass mailing of ballots and applications, and private grants to elections offices that helped progressives get out the vote.

Recent GOP forays into ballot collection include public embarrassments, such as 2018’s debacle in North Carolina, where Republican U.S. house candidate Mark Harris enlisted a Democratic operative with ballot harvesting skills. The caper ended up in voter fraud convictions against the harvester and the election results being tossed out.

Last year, a Republican ward leader in Philadelphia was ousted after it was alleged his campaign went door-to-door signing up mail-in voters, then having their ballots sent to the campaign headquarters.

Colorado and Wisconsin

Other states are just starting to embrace the collection strategy. In Colorado, where lawmakers last year sought to return the all-mail voting state to traditional, voting day elections, Republicans are trying to incorporate ballot collection into their ground game.

“The 2024 election will be our first foray into ballot harvesting,” Colorado GOP party chairman Dave Williams told RealClearInvestigations. Williams is one of several state GOP leaders to confirm that voting mechanisms Republican voters were told just four years ago would ruin the integrity of voting will be embraced by conservative parties and candidates in 2024.

“It’s going to come down to getting enough money to ensure we can implement a [ballot collection] operation,” he said, adding that it will take “thousands” of volunteers to match the Democrats.

In Wisconsin, the Republican Party now sends mail ballot applications to its base voters as soon as early voting begins, encouraging them to cast their ballots from home. Harvesting in Wisconsin has been part of a legal back-and-forth and the courts will eventually determine its legality in the state, which has moved from swing state to reliably Democratic since 2018.

“If it is permitted, we will incorporate that into our ground game,” said Wisconsin state Republican Party executive director Mark Jefferson. “As much as we may not like the expansion of absentee and early voting, we have to use it.”

In a test for 2024, Jefferson said, the party used harvesting in the 2022 state Supreme Court race.

“We turned out our base effectively,” he said. But the party lost both the race and its majority on the court in a progressive voter backlash to the U.S. Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, which had asserted a constitutional right to abortion.

“Over the course of several cycles, I think we can get there,” Jefferson said, optimistic that the party can use collection and other progressive tactics to win elections. “In the meantime, I think we have to push it, but we also need to look for any opportunity to ensure that ballot integrity is still protected.”

The Costly ‘Match Back’ Game

A well-funded harvesting operation has the money to obtain updated “match back” files almost daily during a voting period. These updated voter lists are available to anyone, although a connection or relationship with the election administration office helps pry them loose. The money to pay for them comes from parties and candidates, or in some cases the activist nonprofits deploying ballot collectors.

“Some groups can afford to buy that file every day, especially in the urban areas,” said Michael Der Manouel Jr., former vice chairman of the California Republican Party. “And they can do it from election administrators who care about the outcome of the election, and most of them are Democrats.”

Obtaining the files is eased by a good relationship with the local election administrator, he added. In Wisconsin in 2020, the quest by progressive agents to retrieve the voter file daily was chronicled in a report generated during the state’s legislative inquiry into the November election.

Progressive groups have gained influence over election administrations through private grants, conferences and the designing of election materials including ballot applications and election department websites, all with an emphasis on voter recruitment and repeating Democratic talking points, such as purported “misinformation” and alleged “threats to democracy.”

Speakers at the conferences include representatives from the American Civil Liberties Union and representatives from the progressive group Democracy Now.

Most recently, four progressive nonprofit foundations have pledged to distribute $125 million in grants as The Election Trust Initiative, a subsidiary of the Pew Charitable Trusts, to provide private funding to elections offices over the next five years.

Their mission is to “strengthen the nonpartisan evidence, organizations, and systems that help local and state officials operate secure, transparent, accurate and convenient elections,” according to a press release.

The Biden Administration Wades In

The federal government is bolstering its newly created Election Community Liaison office, an arm of the U.S. Department of Justice, offering a salary of up to $183,000 for hires to, in part, pursue “election offenses.”

A member of President Biden’s cabinet also has connections to the move to change voting. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm in 2020 was on the board of the National Vote at Home Institute, a progressive nonprofit that has successfully pressured states through lobbying and funding to adopt more permissive mail voting. The group has also privately funded public elections departments through its grant program. Her one year on the board coincided with an increase in the institute’s revenue from $1.1 million in 2019 to $8 million during Granholm’s tenure.

Several other Biden administration appointees worked for progressive elections operations including Michelle Obama’s When We All Vote and the Voter Registration Project.

These groups have been part of a push toward mail voting and looser rules regarding ballot collection, combating Republican efforts to limit or regulate those practices.

“Republicans used to own absentee voting,” said Paul Bentz, a political consultant in Arizona, referring to traditional GOP efforts to collect the ballots of the elderly and military service members. “But they’ve given up that advantage.”

Critics of the GOP’s newfound strategy of ballot collection contend that it may be too late, at least to win in 2024.

“The nature of the left is to never stop fighting and usually their fight is smart,” said Scott Walter, president of the conservative Capital Research Center, which studies the influence of nonprofits on politics. “They have multiple think tanks dedicated to nothing but winning elections. And there are no Republican counterparts.”

While Republicans will engage in the same practices as their foes, “harvesting for Republicans won’t work,” said Der Manouel, the former vice chair of the California GOP.

“Republican voters don’t need to have their vote harvested. The only reason it works for Democrats is because they could never turn out their voters. What’s going to happen is Republicans are going to start doing this and find that they don’t have nearly enough ballots to harvest to make a difference.”

– – –

Steve Miller is a writer for RealClearInvesigations.