by Julie Kelly

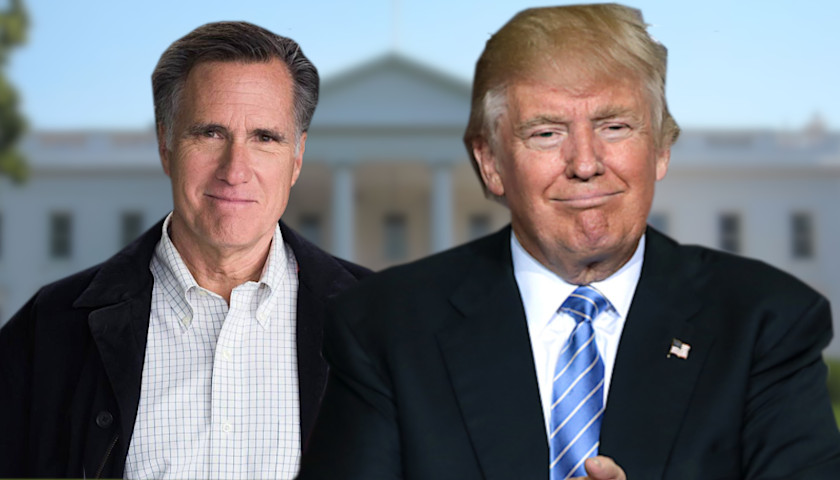

Just as the Republican Party is purging itself of hackneyed lawmakers, bitter neoconservative commentators, and insatiable interventionists, along comes Mitt Romney to remind us of what we definitely are not missing.

In a late New Year’s Day sermon published in the Washington Post, the incoming senator expressed his disappointment in the president and, by extension, in all of us. It was filled with the sort of juvenile platitudes that at one time mollified Republican voters, but now either amuse or enrage them. “A president should unite us and inspire us to follow ‘our better angels.’ A president should demonstrate the essential qualities of honesty and integrity, and elevate the national discourse,” the twice-losing presidential candidate warned. “To reassume our leadership in world politics, we must repair failings in our politics at home. It includes political parties promoting policies that strengthen us rather than promote tribalism by exploiting fear and resentment.”

Romney then proceeded—oddly—to lament Trump’s unpopularity in the world (sorry to disappoint you, Sweden!) and called for a unified Europe. We must defend the press and labor unions, Romney insisted, despite their failings. And he essentially called Trump a racist, sexist, immigrant-hater.

Real original.

The reaction on the Right to Romney’s missive was fast and furious. His niece, head of the Republican National Committee, sided with Trump, calling the opinion piece written by her wayward kin “disappointing and unproductive.” Trump again teased the man he once teased with the prospect of a cabinet position: “Would much prefer that Mitt focus on Border Security and so many other things where he can be helpful. I won big, and he didn’t. He should be happy for all Republicans. Be a TEAM player & WIN!” Trump tweeted on Wednesday morning.

While Donald Trump sharpens his ax to take on impeachment efforts and potential 2020 presidential rivals, he could hardly ask for a better whetting stone than Romney. The incoming Republican senator from Utah is the embodiment of what ailed the establishment GOP for two decades before Trump won the presidency: a pedigreed, wealthy, elegant loser who cowed to pressure from the media and Democrats every time. Their long-standing feud, cataloged by Philip Bump, is a metaphor for the internecine struggle within the Republican Party. Is it Trump’s party or is it Romney’s?

Further, as criticism about Trump’s alleged lack of presidential character rolls on, what does Romney mean by writing, “presidential leadership in qualities of character is indispensable”? And who is Mitt Romney to issue such a warning?

Over his ambitious, self-serving, 25-year career, Romney’s positions on major issues from subsidized health care to abortion to global warming have changed more often than his home address. Faced with skepticism from conservative voters in 2012, he laughably had to declare that he was “severely conservative.” But in 2002, when running for governor of Massachusetts, Romney called himself a moderate with progressive views.

He had no concerns about poor character 11 years ago when he teamed up with then-Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) to pass a universal health care law in that state. Calling him a “collaborator and friend” during the 2007 signing ceremony, Romney lauded Kennedy’s indispensable work behind the scenes to push the not severely conservative government program. He later admired Kennedy’s political skills and called the man who left a young girl to die in a submerged car his “go-to guy” when Romney needed help.

Similarly, Romney had no concerns about Trump’s character when he solicited his endorsement in 2012. Acknowledging his political groveling on a stage shared with his wife and Trump in Nevada before that state’s crucial primary, Romney admitted that “there are some things you just can’t imagine happening in life, this is one of them,” he joked. “Being in Trump’s magnificent hotel and having his endorsement is a delight. I’m so honored and pleased to have his endorsement.” He won that primary a few days later.

But unfortunately, Romney lost the general election in November—and it was that campaign that presented Romney’s own early test of presidential character. The 2012 election was a winnable race for the Republican candidate: The GOP had picked up an astounding 675 legislative seats nationwide, including 63 House districts and six Senate seats, in 2010. Obama’s popularity plummeted in 2011 and early 2012; as the contest between the president and Romney heated up in September 2012, the incumbent’s approval rating stood at 44 percent.

Then, Benghazi happened. Terrorists attacked the U.S. consulate in Libya on the eleventh anniversary of 9/11, killing four Americans including our ambassador. It was clear from the beginning not only that the Obama administration had failed to protect the outpost and the Americans serving there, but that its leading mouthpieces were lying about what happened. In a Rose Garden speech the next day, President Obama never referred to incident as a terrorist attack or to the killers as terrorists.

From the White House podium, press secretary James Carney blamed a “reprehensible and disgusting” video for the attack. When the remains of the fallen were returned a few hours later, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton referred to the “assault” and blamed an “awful internet video that we had nothing to do with.” Susan Rice, the U.N. Ambassador, infamously appeared on five Sunday news shows a few days after the attack to peddle the YouTube video excuse. The press, eager to see Obama reelected, helped push the bogus narrative.

So, what did Romney do? How did the president-in-waiting confront an obvious cover-up about a deadly terrorist attack two months before the election? He caved.

After issuing a quick condemnation on the White House’s handling of the attack, Romney faced harsh criticism by the press and the administration for “jumping the gun.” During the second debate, when moderator Candy Crowley challenged Romney’s (correct) assertion that Obama had not referred to Benghazi as a terrorist attack, the Republican candidate was flat-footed in his response. After that, it was radio silence. Obama’s approval ratings went up, and he won the November election by three points.

Thanks to Romney’s weakness, the nation endured another four years of Obama, which resulted in the Iranian Nuclear deal, the Paris Climate Accord, the Syrian civil war and resulting refugee crisis, and economic stagnation, to name just a few unwanted consequences. In four years, Romney openly criticized Obama once—for the Iran deal and how Americans will “carry the burdens of the millions of illegal immigrants he welcomed.” Obama’s Justice Department delayed pursuing the Benghazi killers, adding to the pain of the victim’s families.

The bottom line is that Romney’s political character is not far removed from Trump’s. Romney changed his views to advance his career; partnered up with dubious characters to make legislative deals; and ridiculed people on the opposite side of the political aisle to curry favor with his base. (Remember his infamous comment about the “47 percent” of the people he suggested could safely be ignored because they don’t contribute to the system, but instead take from it? Romney eventually had to apologize, but it did lasting damage to the Republican brand.)

Yes, he has a lovely wife and family; apparently he has never banged a porn star. But he’s been an ineffectual, if not damaging, political leader who cares more about how to please the Swedes than how to help Americans in Kenosha. A wealthy man at 71, he still can’t resist the attention and power gleaned from public office. It’s a self-serving, not selfless, endeavor.

Trump should welcome Romney’s character challenge not as a test of his fidelity to his wife but as a test of his loyalty to the American people and the issues that matter. In that contest Trump trumps Romney by a wide margin.

– – –