by Carson Holloway

Members of the mainstream media understandably resent President Trump’s description of them as purveyors of “fake news.” After all, they do the public a service by reporting a great deal of true and relevant information. And when they get the facts wrong, they usually correct the record.

Nevertheless, the president’s criticisms of the media resonate with many Americans. For them, the “news” industry is “fake” not in the sense that it tells nothing but falsehoods, but rather in the sense that its self-presentation is fake or phony. The media claim to be disinterested reporters of the facts, but their behavior shows they are far more interested in some facts than in others. This suggests that their main concern is not in uncovering the truth but in telling a certain kind of story.

The “fake news” charge sticks not because of the media’s mendacity but because of their selective curiosity.

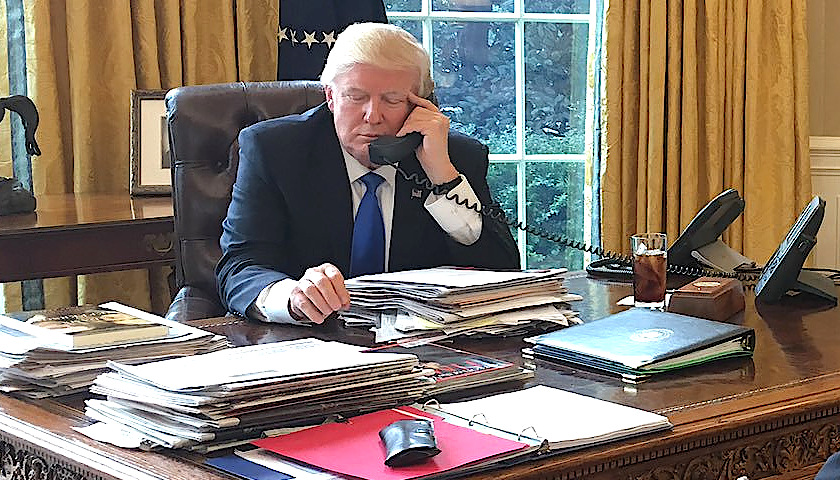

Nowhere has that selective curiosity been more evident than in the coverage of the biggest news story of the last two years: the supposed complicity of Trump and his campaign in Russian efforts to influence the 2016 election. From top to bottom, this story has been shaped powerfully by mainstream news organizations’ extreme lack of interest in certain questions that objectively are interesting and important.

Start at the top. For two years, we have had intense media coverage of the counterintelligence investigation into the Trump campaign carried on by people at the FBI and the Department of Justice. The very existence of this investigation raises an interesting question that has hardly been discussed. It is also one that the media seems completely uninterested in answering: What did President Obama know about this investigation? To what extent was he briefed on it? What role, if any, did he play in deciding its scope?

These queries obviously will be of great interest to future historians. Journalists commonly claim to write the first draft of history. It is strange, then, that they have exhibited so little interest in these important questions.

Moreover, a dispassionate observer, confronted with this striking lack of curiosity, cannot help but wonder whether it is fostered by some partisan interest. After all, the facts about President Obama’s relationship to the investigation, whatever they may be, would raise questions that Obama defenders would rather avoid.

If President Obama did not know about the opening of the investigation, it might suggest that his high-ranking subordinates had gone rogue, and that his administration was not really under his control. It would also raise a question about whether the investigation was really necessary for national security purposes. It is hardly credible, after all, that the possible Russian penetration of a major presidential campaign was not important enough to tell the president about it.

On the other hand, what if President Obama knew about and approved of the investigation? If so, he might sincerely have believed it was justified and necessary.

Nevertheless, insofar as more than two years of investigation have turned up no solid public evidence of President Trump’s involvement in “Russian collusion,” it might appear to some that he was weaponizing the nation’s law-enforcement and counterintelligence services against a political opponent.

The most hardcore opponents of President Trump like to raise the possibility that he has obstructed justice and then note that the House Judiciary Committee treated this as one of the impeachable offenses of Richard Nixon in the Watergate affair. The articles of impeachment against Nixon, however, also included the charge that he had “misused the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Secret Service, and other executive personnel, in violation or disregard of the constitutional rights of citizens, by directing or authorizing such agencies or personnel to conduct or continue electronic surveillance or other investigations for purposes unrelated to national security, the enforcement of laws, or any other lawful function of his office.”

One could wonder, then, whether President Obama himself strayed into Nixonian territory. It is understandable, of course, that his supporters would not want to raise such possibilities. But one would expect that an ostensibly nonpartisan press would want to find out all the facts so that the public could make an informed judgment.

If we move from the top of the “Russia collusion” investigation to its ground level, we find a similar selective curiosity on the part of the media. The American press has been keen to hear directly from Trump associates like Michael Cohen, and to detail the actions of others such as former campaign manager Paul Manafort and former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn. No person, however, is more central to this story than Christopher Steele, the former British spy who compiled the famous “dossier” of material purporting to show Trump’s connections to Russia. Nevertheless, Steele has remained almost entirely silent for the last two years, and the media have made very little effort to penetrate his silence or to inquire into the possible reasons for it.

According to news reports, Steele was ardently concerned that Donald Trump not be elected president, apparently believing that Trump somehow was compromised by his connections to Russia. In light of such grave dangers, one would expect that Steele would want to appear before the public, submit to interviews, and explain just how he knew what he alleged in his dossier. Strikingly, he instead has said nothing of substance.

Steele might have good legal reasons for his silence. He is being sued for libel. He was reportedly interviewed by Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigators, and it may be that Mueller asked Steele to remain silent until his investigation is complete.

Nevertheless, when the central figure in an important story remains stone silent, the media generally focus relentlessly on the silence in an effort to get that figure to say something. Practically everyone agrees that there should be some rational, evidence-based effort to verify the contents of Steele’s dossier. The obvious first step in that process would be to get Steele to speak publicly and possibly submit to interviews in which he could be questioned about how he knows what he claims to know.

The media have not done this in Steele’s case. One cannot help but wonder whether certain partisanship has influenced their lack of interest. After all, it is very likely that Steele can say nothing further to corroborate his claims—either because there is no corroboration, or because detailed corroboration would require him to reveal his “sources and methods.” In that case, the dossier—which the media has vested with so much importance, and in which Trump’s enemies have invested so much hope—would appear unconfirmable and therefore a flimsy basis for two years of public hysteria. Here again, the media’s lack of interest tracks very closely with the kind of things Trump’s enemies would rather not talk about.

It does not go too far to say that the media’s handling of the “Russia collusion” story has given the whole affair an Orwellian quality. The issue has been discussed with more intensity than practically any other news story in American history, yet obvious questions about it go unexplored and even largely unasked. As long as this continues, many Americans will continue to view the media as “fake news.”

– – –

Carson Holloway is a visiting scholar in the B. Kenneth Simon Center for Principles and Politics at the Heritage Foundation (heritage.org) and the author of Hamilton versus Jefferson in the Washington Administration.