by Mark Sherman, Lisa Mascaro and Mary Clare Jalonick

WASHINGTON, D.C. (AP) —Judge Amy Coney Barrett’s Supreme Court nomination cleared a key hurdle Thursday as Senate Judiciary Committee Republicans powered past Democrats’ objections in the drive to confirm President Donald Trump’s pick before the Nov. 3 election.

The panel set Oct. 22 for its vote to recommend Barrett’s nomination to the full Senate for a final vote by month’s end.

“A sham,” said Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn. “Power grab,” decried Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn. “Not normal,” said Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill.

“You don’t convene a Supreme Court confirmation hearing, in the middle of a pandemic, when the Senate’s on recess, when voting has already started in the presidential election in a majority of states,” declared Sen. Chris Coon, D-Del.

But Republicans countered that Trump is well within bounds as president to fill the court vacancy, and the GOP-held Senate has the votes to push Trump’s nominee to confirmation.

Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, said he understands Democrats’ “disappointment, but I think their loss is the American people’s gain.”

Barrett’s confirmation to take the seat of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is poised to lock a conservative majority on the court for years to come. The shift would cement a 6-3 court in the most pronounced ideological change in 30 years, from the liberal icon to the conservative appeals court judge.

The committee’s session Thursday was without Barrett after two long days of public testimony in which she stressed that she would be her own judge and sought to create distance between herself and past positions critical of abortion, the Affordable Care Act and other issues.

Instead, outside witnesses testified, including representatives of the American Bar Association’s standing committee which gave Barrett its highest “well qualified” rating — but not unanimously. Barrett is the first high court nominee since Justice Clarence Thomas not to earn a unanimous rating.

Kristen Clarke, the president of the Lawyers Committee on Civil Rights opposing Barrett’s nomination, said the judge’s unwillingness to speak forcefully for the Voting Rights Act should “sound an alarm” for Americans with a case heading to the high court.

“Our nation deserves a justice who is committed to preserving the hard-earned rights of all Americans, particularly the most vulnerable,” said Clarke.

Retired appellate court Judge Thomas Griffith assured Barrett is among justices who “can and do put aside party and politics.”

Among those testifying was Michigan primary care doctor Farhan Batti who warned of the toll on his patients if the Supreme Court does away with the health care law and Crystal Good, a writer from West Virginia, who told the very personal story of seeking an abortion as a sexually-abused teen-ager.

“Hear us when we ask you not to approve this nomination,” she implored the senators.

Facing almost 20 hours of questions from senators, the 48-year-old judge was careful not to take on the president who nominated her.

She skipped past Democrats’ pressing questions about ensuring the date of next month’s election or preventing voter intimidation, both set in federal law, and the peaceful transfer of presidential power. She also refused to express her view on whether the president can pardon himself.

When it came to major issues that are likely to come before the court, including abortion and health care, Barrett repeatedly promised to keep an open mind and said neither Trump nor anyone else in the White House had tried to influence her views.

Nominees typically resist offering any more information than they have to, especially when the president’s party controls the Senate, as it does now. But Barrett wouldn’t engage on topics that seemed easy to swat away, including that only Congress can change the date that the election takes place.

She said she was not on a “mission to destroy the Affordable Care Act,” though she has been critical of the two Supreme Court decisions that preserved key parts of the Obama-era health care law. She could be on the court when it hears the latest Republican-led challenge on Nov. 10.

Barrett is the most open opponent of abortion nominated to the Supreme Court in decades, and Democrats fear that her ascension could be a tipping point that threatens abortion rights.

Republican senators embraced her stance, proudly stating that she was, in Graham’s words, an “unashamedly pro-life” conservative who is making history as a role model for other women.

Barrett refused to say whether the 1973 landmark Roe v. Wade ruling on abortion rights was correctly decided, though she signed an open letter seven years ago that called the decision “infamous.”

In an exchange with Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., Barrett resisted the invitation to explicitly endorse or reject the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s comments about perpetuating “racial entitlement” in a key voting rights case.

“When I said that Justice Scalia’s philosophy is mine, too, I certainly didn’t mean to say that every sentence that came out of Justice Scalia’s mouth or every sentence that he wrote is one that I would agree with,” Barrett said.

One of the more dramatic moments came late Wednesday when Barrett told California Sen. Kamala Harris, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, that she wouldn’t say whether racial discrimination in voting still exists nor express a view on climate change.

Along with trying to undo the health care law, Trump has publicly stated he wants a justice seated for any disputes arising from the election, and particularly the surge of mail-in ballots expected during the pandemic as voters prefer to vote by mail.

Barrett testified she has not spoken to Trump or his team about election cases, and declined to commit to recusing herself from any post-election cases.

In 2000, the court’s decision in Bush v. Gore brought a Florida recount to a halt, effectively deciding the election in George W. Bush’s favor. Barrett was on Bush’s legal team in 2000, in a minor role.

– – –

Mark Sherman, Lisa Mascaro and Mary Clare Jalonick are reporters for The Associated Press. AP writers Matthew Daly and Jessica Gresko in Washington, and Elana Schor in New York contributed to this report.

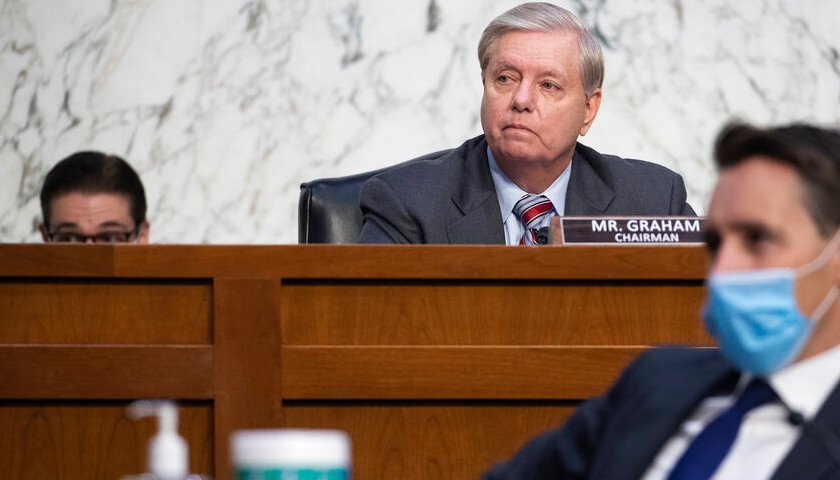

About the Headline Photo: Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett speaks during a confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Wednesday, Oct. 14, 2020, on Capitol Hill in Washington. (Anna Moneymaker/The New York Times via AP, Pool)