by Greg Piper

A proposal in a Stanford University journal for “news source trustworthiness ratings” would, if it advances, be like a digital reboot of the CIA’s psychedelic mind-control experiments from the Cold War era, says a former State Department cyber official who now leads a online free speech watchdog group.

The psychological manipulation used in the experiments – known as Project MK-ULTRA and the subject of congressional hearings in 1977 – is reflected in the Journal of Online Trust and Safety study, conducted by researchers at U.S. and Italian universities, says Mike Benz, the former State Department official who now leads the watchdog group Foundation for Freedom Online.

“The whole point” of the study “is you don’t even need fact-checkers to fact-check the story,” a labor-intensive endeavor across the internet, if social media platforms simply apply a “scarlet letter” to disfavored news sources, Benz told Just the News. By creating “the appearance of having done a fact-check, it’s deliberately fraudulent.”

Benz said he’s in discussions with House Appropriations Committee staff on attaching a rider to funding bills for federal agencies such as the National Science Foundation that would prohibit them from funding institutions that promote such activities.

“What if Raytheon was doing this?” he asked rhetorically, referring to the defense contractor. Stanford, which participated in MK-ULTRA, should have to “pay for their own dirty work” without taxpayer subsidies, Benz (pictured above) said. The journal did not respond to queries.

Study coauthor Gordon Pennycook, who joined Cornell University as a psychology professor this summer after submitting the paper as faculty at Canada’s University of Regina, rebukes the MK-ULTRA comparison.

“Our research shows that trustworthiness ratings have a psychological impact. Nothing about what we find necessitates a particular source for such ratings,” Pennycook told Just the News in an email. “Nor does it necessitate a particular way of implimenting [sic] such ratings.”

He said there was a “mountain of difference between ‘people use the ratings if you provide them’ and ‘mind control,'” which would also apply to Just the News reporting and Benz’s attempts to “persuade people to agree with him about whatever issues he cares about.”

The journal was launched nearly two years ago by the Stanford Internet Observatory, a leader in the public-private Election Integrity Partnership that mass-reported alleged election misinformation to Big Tech and Virality Project that sought to throttle admittedly true COVID-19 content.

Its stated purpose is to study “how people abuse the internet to cause real human harm, often using products the way they are designed to work,” the editors wrote in the inaugural issue, which included a paper on the intersection of hate speech and misinformation about “the role of the Chinese government in the origin and spread of COVID-19.”

The trustworthiness-ratings study was published in the most recent issue of the journal, in April, but appears to have drawn little attention, with its ResearchGate page only tracking two citations. Its only mention on X, formerly Twitter, is an April 27 thread with 22 shares by lead author Tatiana Celadin of Ca’Foscary University.

Happy to share that our new paper on misinformation with @ValerioCapraro, @GordPennycook and @DG_Rand is out in @journalsafetech!

Link: https://t.co/MoLHnTwj5x

We study a new scalable intervention by focusing on displaying the rating of news sources.

Check below what we found! pic.twitter.com/tiQr4r43AA— Tatiana Celadin (@TatianaCeladin) April 27, 2023

It lauds the work of self-described professional fact-checkers without noting their less-than-noble recent history. Many COVID claims have been validated or judged debatable after fact-checkers declared them misinformation, and an American Medical Association journal recently published a paper that still deems the lab-leak theory misinformation.

Snopes.com, perhaps the first self-described fact-checker, has repeatedly flagged the explicit satire of The Babylon Bee. It also retracted 60 articles by its cofounder David Mikkelson in 2021, published during its Facebook fact-checking partnership, following a BuzzFeed News investigation that found 54 were plagiarized.

Former business associates also sued Mikkelson for financial mismanagement, alleging in part he used company money for “lavish” vacations, and Snopes itself sued its other cofounder, his ex-wife Barbara, for “receipt of stolen funds” from its advertising partner.

“Professional fact-checking of individual news headlines is an effective way to fight misinformation, but it is not easily scalable, because it cannot keep pace with the massive speed at which news content gets posted on social media,” the study authors write.

News may be labeled false “after it has already been read by thousands, if not millions, of users,” and users might wrongly assume news not marked as false is true, according to the study. “Corrections often reach a different audience from the one reached by the original, untagged, headline,” and “a substantial proportion of people” don’t trust fact-checkers.

Though the “wisdom of crowds” compares favorably to professional fact-checkers, “laypeople ratings will also experience a systematic delay relative to the time when a news story gets published,” the authors say.

For the experiment, they asked about 1,600 U.S.-based participants provided by online survey company Lucid what kinds of content they consider sharing, such as political and sports news, and what social media they use, then randomly assigned them to three conditions.

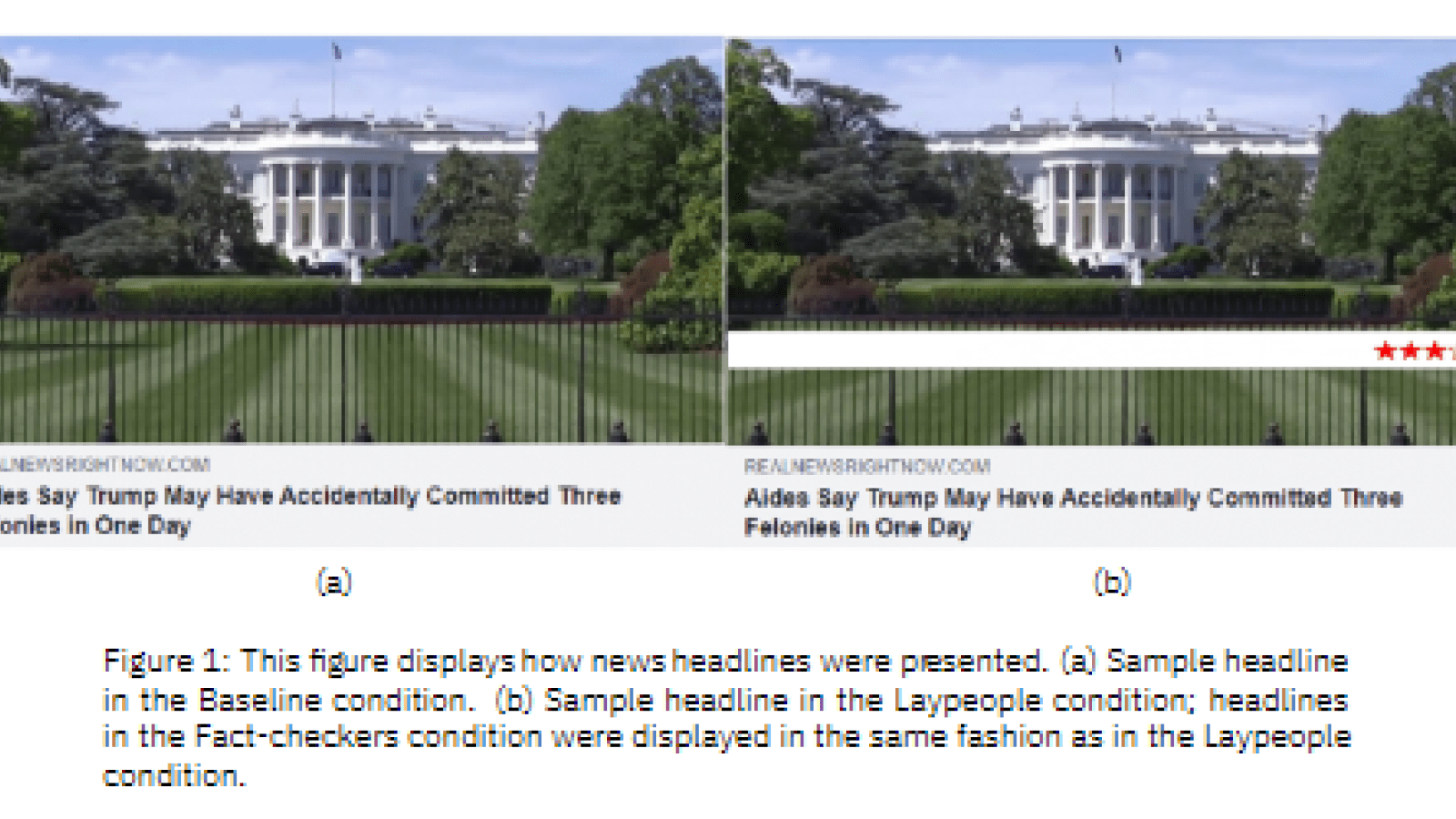

The “baseline” group was shown 24 news headlines on Facebook, half each pro-Democrat or pro-Republican, split between true and false. They were then asked on a 1-5 scale how likely they were to share it.

The “fact-checkers” group was also told they would see a trustworthiness rating for the source on some headlines, as decided by “eight professional fact-checkers,” then shown a “banner” with its rating. The “laypeople” group swapped in about 1,000 laypeople for fact-checkers.

The results: The difference in willingness to share true relative to false headlines went up “significantly” among both the fact-checker and laypeople groups. And false-headline-sharing went down significantly for each, with a much larger effect among the former group. Sharing of true headlines wasn’t affected for either group.

The authors observed a “spillover effect” for headlines without a rated source, which also exhibited higher “sharing discernment,” suggesting that users who see rated sources “reflect on source quality more generally.”

The paper does acknowledge the scalable approach has “the downside of being coarse, as low-credibility sources sometimes publish accurate news and high-credibility sources sometimes publish inaccurate news,” and that “these ratings can be altered by interested parties to damage their competitor or advantage themselves,” undermining their own trustworthiness. That only reinforces, however, that this “should be accompanied with other interventions” against misinformation.

Benz noted the authors’ stated concerns that “exposure to even small amounts of misinformation … can increase beliefs even for extremely implausible political claims, and COVID-19 misinformation can reduce vaccination intentions.”

The “sole and express purpose” of “The Stanford Star,” in Benz’s words, is “psychologically priming people to discredit a news source [researchers] can’t get banned but want to make sure no one believes,” hence creating a “whitelist media cartel.”

This “censorship as a service” gives social media companies “a quick and easy way to throttle all news content from any website” given a low rating,” he said.

– – –

Greg Piper has covered law and policy for nearly two decades, with a focus on tech companies, civil liberties and higher education.

Photo “Mike Benz” by Mike Benz. Background Photo “Stanford University” by Jawed Karim. CC BY-SA 3.0.