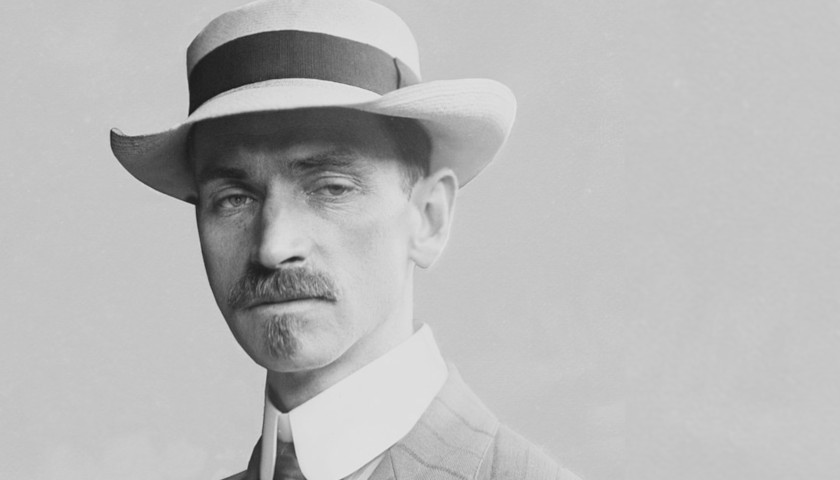

Bicycles, motorcycles, blimps, and planes – Glenn Hammond Curtiss was “always eager for speed” and “obsessed with the idea of traveling fast,” according to an autobiography Curtiss wrote with friend Augustus Post. Before the age of 30, Curtiss received the informal title of “fastest man on earth” for his motorcycle races.

Born May 21, 1878 in Hammondsport, New York, Curtiss experienced a number of family tragedies at a young age. His father died when he was just four years old, and his mother was left to raise him and his sister, Rutha, who became sick with meningitis and quickly went deaf from the illness. His mother, Lua, moved the family to Rochester so Rutha could attend a school for the deaf.

Curtiss was an exceptional student, but his formal education ended after eighth grade, according to a biography of his life written by David Langley and peer-reviewed by aviation historians. He picked up a number of odd-jobs to help with family expenses, including a position with the Eastman Kodak Company and as a delivery boy for the Western Union.

By his teenage years, “bicycles and speed had become a near-obsession” with Curtiss and he became a champion racer at county fairs throughout the state, the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum says of its namesake. His grandmother played an important role in his early life and purchased for Curtiss his first bicycle, according to the National Aviation Hall of Fame of which Curtiss is a member.

Like the Wright brothers, Curtiss began his own bicycle business, designing, building, and repairing the vehicles for the residents of Rochester. The business became so successful that Curtiss opened up branch stores in Bath and Corning, New York.

Curtiss was “fascinated by the possibilities” after the advent of the motorized engine in the United States, and he began building and attaching his own engines to bicycles, essentially converting them to motorcycles. With the support of friends and bankers, Curtiss launched the G.H. Curtiss Manufacturing Company in 1902 and began manufacturing his own motorcycles, called the “Hercules” motorcycle.

In 1903, Curtiss was named the first American Motorcycle Champion for setting a world record mile and frequently competed against and defeated powerhouses Harley Davidson and Indian, according to the Smithsonian.

“He quickly earned a reputation for designing powerful, lightweight motorcycle engines,” the Smithsonian says.

That’s when, in 1904, he was approached by balloonist Thomas Scott Baldwin, who ordered a V-twin motorcycle engine from Curtiss to power America’s first successful dirigible. At the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, Baldwin flew his airship, called the “California Arrow,” and it was powered by an engine designed by Curtiss.

Baldwin and Curtiss became close friends after that, and Baldwin moved his operation to Hammondsport, marking the start of Curtiss’ career in aviation.

Aviation

By 1907, Curtiss had attracted the attention of famed inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who was forming the Aerial Experiment Association. This was after Curtiss raced his V-8 powered motorcycle, the world’s first, at a speed of 136.36 miles per hour at a measured-mile run in Ormond Beach, Florida. He was henceforth known as the “fastest man on earth.”

So he joined Graham Bell’s group of inventors, which included F.W. “Casey” Baldwin, John McCurdy, and U.S. Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge. Along with the Wright brothers, the AEA was one of the first group’s in North America to build and fly airplanes.

After building two successful planes called the “Red Wing” and the “White Wing,” Curtiss and the AEA built a third plane called the “June Bug.” The plane was so successful in testing that Curtiss decided to enter it into the Scientific American Trophy Competition of 1908. On July 4, 1908, Curtiss piloted the “June Bug” across Pleasant Valley for a distance of 5,090 feet, winning him the first leg of the competition. The flight of the “June Bug” was the “first officially-recognized, pre-announced, and publicly observed flight in America,” according to the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum.

The AEA disbanded in 1909, but Curtiss secured the group’s designs and patents. Later that year, he set a world record after piloting his “Golden Flyer” for a distance of 24.7 miles and won the second leg of the Scientific American Trophy Competition. He then competed against Europe’s top aviators in Rheims, France, where he won the Gordon Bennet Cup speed race.

In 1910, the New York World Newspaper offered a $10,000 prize for the first successful flight between Albany and New York City along the Hudson River, and Curtiss’ “Hudson Flyer” was the one to do it.

“It was his much-publicized Albany to New York flight that established the aeroplane as having some practical value. It was even suggested that it might have a wartime use,” the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum says of the flight.

Indeed, Curtiss pioneered the idea of seaplanes and flying boats for use by the U.S. Navy, and gave the first demonstration of aerial bombings to Army and Navy officials at Keuka Lake. He’s often remembered as the “Father of Naval Aviation.”

His final aerial achievement came in 1919 when “flying boats” he designed were manned by U.S. Navy pilots and became the first to fly across the Atlantic Ocean.

“When it comes to crossing the Atlantic, many people think that Charles Lindbergh was the first to do so in 1927. As marvelous as his achievement was, he was just the first person to fly solo from New York to Paris,” Langley explains.

Curtiss left the aviation business in 1921 and moved to Florida, where he became a land developer and helped build the cities of Hialeah, Miami Springs, and Opa-Locka.

Conflicts with the Wright Brothers

Curtiss and the Wright brothers frequently butted heads. In one case, the Wrights sued Curtiss for his development of ailerons, which the Wrights claimed was a rip-off of their patented wing-warping concept.

Early in his aviation career, however, Curtiss made two attempts to work with the Wright brothers. In 1906, he sent a letter to the Wright brothers asking if they were interested in purchasing one of his engines, but they declined. He wrote them again in 1907, this time offering one of his engines for free, but they again refused.

The Wright brothers had already completed their first successful flight at this time, but they operated in secret, didn’t allow any public viewings of their flight, and had a deep distrust of the press. The obvious result was that the Wright brothers received little public attention.

As the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum puts it, “it was a mistake that would cost them dearly.”

In 1914, Curtiss set out to prove that it was actually Samuel P. Langley, not the Wright brothers, who invented the first successful aircraft capable of sustained flight. The claim resulted in three decades of arguments between the Smithsonian and the Wright family over who had invented the first successful plane. In 1943, the Smithsonian concluded that the “Wright Flyer” was the first, and the plane now hangs in the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum.

Curtiss and the Wright brothers had a number of patent disputes that were finally put to rest by the U.S. government when it offered both parties a cash settlement. In exchange, the military was able to work with both parties to help with its aviation needs.

Curtiss’ life was cut short when he died at the age of 52 in 1930 while undergoing surgery for appendicitis.

– – –

Anthony Gockowski is managing editor of Battleground State News, The Ohio Star, and The Minnesota Sun. Follow Anthony on Twitter. Email tips to [email protected].