by Adrian Karatnycky

It’s a good time to be a coot, especially an old one. Old coots rule the roost (or more accurately, the nest) in the world’s most powerful and populous countries.

The leaders of the nine most populous countries in the world are today all led by men in their seventies and eighties. U.S. President Joe Biden is 80 years old as is the president of Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari. President Lula of Brazil is 77. Pakistan’s president Arif Alvi is 73 and its prime minister is 71. Narendra Modi of India is 72. The British monarch, Charles III, was coronated at the age of 74. Vladimir Putin is another septuagenarian, as is Xi Jinping who turns 70 this week. Mexico’s President Obrador and Turkey’s President Erdogan will join him this year. Pope Francis heads a UN member state at age 86, a post his predecessor had the temerity to leave when he was a year younger. As if to underscore the predominance of aged leaders, UN General Secretary António Guterres is 74.

In the U.S. the gerontocracy rules in all three branches of government. The Supreme Court is in the main a vast retirement community. Seventy-seven-year-old Donald Trump is the most likely challenger to the aged Joe Biden, while nearly a quarter of the U.S. Congress and more than a third of the U.S. Senate is over the age of seventy.

Taken together, elders govern us as well as over half the world’s population. And then there is the ongoing vigorous influence exerted by Henry Kissinger, 100, and George Soros, Warren Buffett, and Rupert Murdoch, all ninety-two.

Truly, we live in the Age of the Coot.

In the 1970-80s, old age signaled the moribundity of a political system. The world poked fun at Spain’s Francisco Franco and the Soviet Politburo. But Brezhnev was 75 when he died and in his early 70s when the jokes first began. Konstantin Chernenko, his successor, was 73. And Yuri Andropov was still in his sixties when I discussed his brief accursed reign in an American Spectator cover story, “The Sickness of Comrade ’Dropoff” (TAS, May 1984). Sure, jokes about the age of our leaders still abound, but the tone of mainstream media is predominantly deferential. Those holding power are respected by many, even in our polarized democracy.

Several years ago, Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel controversially made the case for why he wishes to die at age 75. He argued that the morbidities associated with advanced years on average come at a high cost to both society and to the elderly individual. But voters aren’t buying it. They continue to place vast political power in the hands of, shall we say, “seasoned” leaders.

What accounts for this remarkable phenomenon? To be sure, part of the answer is that some on this list are dictators, who perpetuate their rule by amending constitutions to ensure eternal rule. But senior citizen leaders are as much a phenomenon of competitive electoral systems. In such democratic systems, aged leaders provide a source of comfort: their message to the rest of us is that you can be productive, healthy, and make a difference as you approach or exceed life expectancy. Average life spans are expanding and the quality of elderly life for the well-off is improving amid new medical and pharmaceutical breakthroughs. As a result, voters seem to agree that their elderly leaders remain ready for prime time.

There are additional reasons for the appeal of elderly leaders. Voters crave predictability and familiarity as technological and environmental changes wreak havoc to daily life. Moreover, as Andy Warhol prefigured, celebrity and fame extinguish themselves quickly and we crave well-worn, boringly familiar faces as fixed markers in a shifting landscape. In a world of endless crises, elderly leaders, too, suggest probity and stability: an unsteady hand means a steady leader. Additionally, as the voter base ages, retirees and the elderly are allying with middle-age voters contemplating old age in a unified electoral bloc that sees older leaders as guarantors of the growing needs of an aging population.

In the last century the average age of a U.S. president at inauguration was just under 55; in our century it has risen by nearly eight years and is likely to climb in the event of a Biden-Trump final. Increasingly, at home and abroad, the election of young leaders is a rarity, especially in presidential systems.

In this context, I can understand the impatience and trepidation of the young. Now in my sixties, I remember at age thirty, and in a new job in D.C. quietly resenting a well-paid consultant, then in his mid-seventies. Why was he there? Why was he taking the place of someone equally competent but more vigorous? Then I learned about my colleague’s past, his adventures as a spy in the Second World War and in post-war Central Europe, of his books and essays, and came to respect his experience, wit, elegance, and counsel.

Still, there is an inherent tension in our state of affairs: The young who want to be in on the action and wait impatiently for an opening to realize their corpulent ambitions. That, as much as the brilliant writing, helps explain why Succession was both such a hit and the television series emblematic of the Age of the Coot.

Hungry, ambitious, and talented young leaders wait in the wings while their elderly superiors get regular medical checkups, pop statins, and Beta-blockers in the morning, and just carry on. Time is running out on them. Not on the old, but on the young … and the anxiety is palpable as government by AI approaches.

– – –

Adrian Karatnycky is a contributor to The American Spectator and was at Woodstock. The first one.

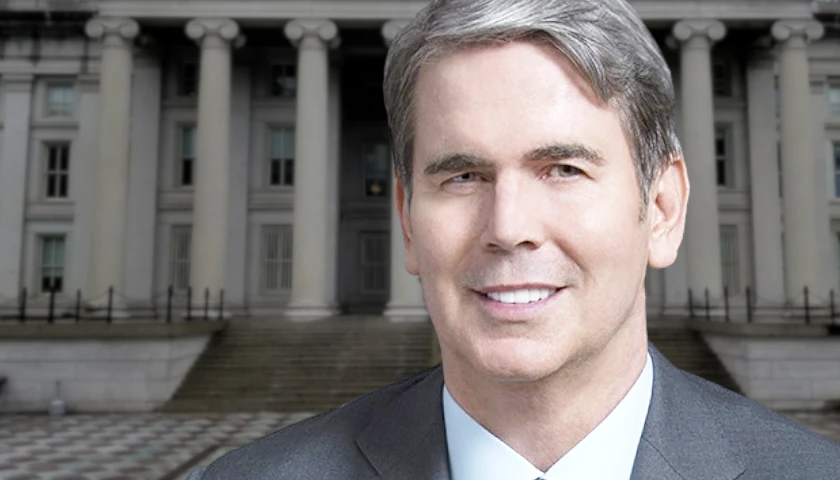

Photo “Joe Biden” by The White House.