by Mark W. Hendrickson

Reports about ESG — “environmental, social, and governance” scores that progressive activists, money-management firms, and government agencies (namely, the Securities and Exchange Commission) assign to corporations — have become nearly ubiquitous in the news. There is even a website, esgnews.com, that keeps track of the latest ESG-related developments.

Recently, Vanguard, the gigantic mutual-fund investment firm, announced that it is increasing “its offering of passive ESG funds in Europe.” Vanguard is just one of numerous examples in the news that could be cited.

On the plus side, governors, state treasurers, and state attorneys general are pushing back against ESG bullies. Republican Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich wrote a blistering commentary in the Wall Street Journal denouncing BlackRock and other “woke asset managers” for abandoning their fiduciary duties to their clients by focusing more on investing in corporations with high ESG scores than in the most profitable companies.

The SEC is leading the Biden administration’s push for all publicly traded companies to publish ESG “disclosures.” Much as the EPA exceeded its statutory authority in trying to regulate fossil fuel companies out of existence before being rebuked by the Supreme Court in this year’s West Virginia v. EPA decision, the SEC appears to have exceeded its statutory authority to “protect investors, maintain fair … markets, and facilitate capital formation” by mandating the publication of highly subjective ESG scores that obviously discriminate against certain companies, most notably the entire fossil fuels industry.

Before taking a closer look at the components of ESG scores, let’s examine the background of this movement.

ESG scores, which were first proposed in 2004 by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, are the latest iteration of the century-old corporate social responsibility (CSR) movement. To understand ESG, we should understand the CSR ideology from which it evolved.

Investopedia says that CSR “helps a company be socially accountable to itself, its stakeholders, and the public” and that CSR helps companies be aware of their impact “on all aspects of society, including economic, social, and environmental.” How far-reaching — and how vague and fuzzy.

The basic problem is that the concept of CSR is highly subjective. It all depends on what any particular advocate of CSR expects or wants corporations to do for the alleged betterment of society. What tends to distinguish the most vocal advocates of CSR is that they generally operate outside of the corporations that they are trying to influence. In fact, most of them have no experience in business. Instead of enduring the rigors of marketplace competition, they prefer the ease of being armchair quarterbacks, presumptuously telling businesses what they should do.

Traditionally, in our (mostly) free-market economic system, corporations’ stakeholders included the corporation’s customers, shareholders (owners), and employees. CSR ideologues reject such a circumscribed, well-defined list of stakeholders. They argue that “society” itself is a stakeholder — and then they presume to speak for society, demanding that corporations alter their business practices, revise their product lines, reallocate their capital, and more in order to achieve the CRS advocates’ goals. Here one can see plainly the CSR crowd’s anti-capitalist antipathy for private property. To them it seems perfectly normal and acceptable that people like themselves, who neither own a business nor work for a business, should have as much or more say about corporate policies than the business’s shareholders, customers, and employees.

These activists play hardball by bullying corporate leaders into making concessions using threats of bad publicity. One wonders, in these cases, where the legal line between free speech and extortion lies. Clearly, outside activists have little respect for the property rights of the legal owners of the corporation when they attempt to hijack a corporation to promote their favored political goals.

The current guise adopted by the CSR folks is the above-mentioned ESG. It has become a blunt instrument used to punish targeted businesses by coercing them into adopting needlessly costly policies or by overtly steering capital away from them.

Brnovich characterizes ESG as “left-wing.” A nonpartisan report from Yahoo Finance states that BlackRock (one of the world’s largest asset managers) and cohorts embraced ESG “in response to pressure from the political left.” These characterizations are valid, for both CSR and ESG are fronts in the traditional war of the collectivist/socialist left against private property. Those pushing a CSR or ESG agenda want there to be centralized political control over other people’s property.

In the area of the environment, today’s activists and elite money managers tend not to focus on pollution. Indeed, that would be mostly superfluous, given the strict environmental regulations with which American businesses already comply. Instead, their scoring system penalizes both private businesses and state governments for the “sin” of using or developing fossil fuels. Thus, ESG scores give states such as West Virginia lower creditworthiness scores despite high bond ratings. And companies that produce fossil fuels, or even companies that deal with fossil fuel companies, are given low scores designed to discourage anyone from lending capital to them. In other words, they are trying to asphyxiate such companies by denying access to financial oxygen — i.e., capital.

ESG is an even bigger farce when it claims to seek social improvements. Today, many American citizens are struggling under soaring gasoline prices and rising heating and cooling costs due to the anti–fossil fuel policies of the Biden administration and their ESG allies. Perversely, ESG activists use low social scores to hamstring the very companies that could produce the reliable, affordable energy that Americans so desperately need. If anyone deserved low social scores, it would be the ESG advocates who are crippling the production of the very fuels that Americans so badly need.

As for governance, pressures from the self-anointed ESG graders may, in fact, cause corporate leaders to commit more errors of governance rather than fewer — much to the detriment of shareholders, employees, and customers. For example, demanding that corporations choose officers and directors on a basis of strict quotas of various demographic slices can hurt a corporation by obliging it to bypass individuals with demonstrated excellence simply because they happen to be of a “wrong” gender or race.

A glaring weakness of governance scores is that they omit consideration of one of the more potentially damaging types of poor corporate governance — i.e., when corporate leaders take sides on controversial public issues. Giving one’s personal endorsement and support to one side of a public policy issue is both a fundamental right and, you could argue, a moral duty. But political advocacy should take place on an individual level, not as an “official” corporate position.

It is presumptuous, if not arrogant, for a corporate CEO to assert that “the corporation” agrees with a particular “woke,” Democratic policy when a significant portion of a company’s customer base, employees, and shareholders are Republican, “unwoke,” and personally opposed to that policy. Two prominent examples of such foolish misgovernance are the following: first, the decision in 2021 by the commissioner of Major League Baseball (MLB) to move the All-Star Game out of Atlanta, thereby taking a partisan position on a Georgia election law and alienating many fans; second, this year’s fiasco when the Disney CEO announced that the Walt Disney Co. opposed a new Florida law that prohibits the teaching of sexual identity to children before the fourth grade in an age-inappropriate way. In both cases, the leaders of MLB and Disney gratuitously offended a large number of their legitimate stakeholders. And for what? To placate outside activists who often have zero actual stake in the corporation.

Bottom line: A corporation can’t be all things to all people. To survive and to prosper and to be accountable to those to whom they have fiduciary and moral responsibilities — i.e., their shareholders and employees — corporations need to focus on satisfying their customers. To get swept up in the latest CSR or ESG fad is bad business. By pursuing partisan political goals instead of traditional business goals, business leaders alienate some consumers, demoralize or anger some employees, and poorly serve their shareholders. Since consumers, employees, and shareholders are the members of society that a business affects most directly, it follows that sacrificing their welfare in the name of some activists’ ideological causes hurts society. In practice, ESG can be very antisocial.

– – –

Mark Hendrickson is an economist who retired from the faculty of Grove City College in Pennsylvania, where he remains fellow for economic and social policy at the Institute for Faith and Freedom. He is the author of several books on topics as varied as American economic history, anonymous characters in the Bible, the wealth inequality issue, and climate change.

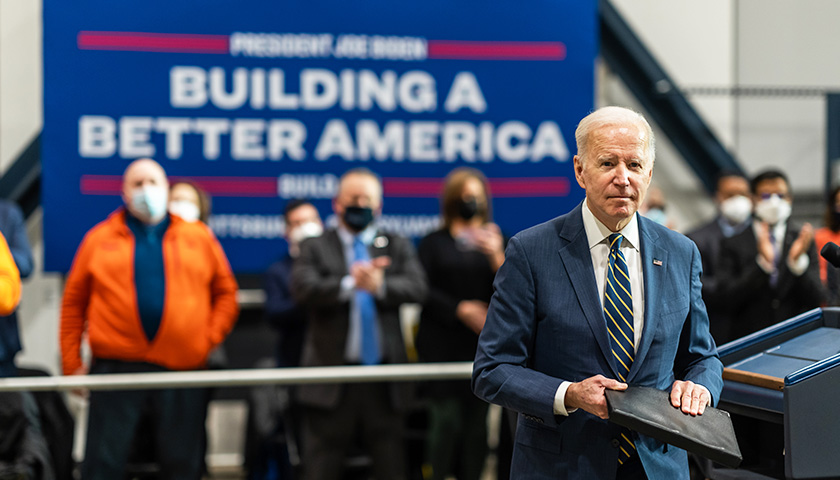

Photo “Joe Biden” by The White House.