by Robert Romano

The U.S. trade in goods deficit with China is down 10 percent in the first six months of 2019, or $18.8 billion, compared to 2018, according to the latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

And that’s with the 10 percent tariffs President Donald Trump slapped on $200 billion of goods and 25 percent on $50 billion that was in place until May. Then, Trump raised the tariff to 25 percent for the $200 billion and in July he added another 10 percent tariff on the remaining $300 billion of goods, bringing it to a total of almost $550 billion of goods that are now taxed.

In June, the first month of the increased tariff, imports from China actually dropped 0.7 percent, which is significant. In all of the data going back to 1985, imports from China have never dropped in the month of June, so there’s a definite impact taking place.

Overall imports from China for the year are already down $30 billion this year. At the current pace, exports to the U.S. could drop by $66.5 billion, or 12 percent this year. That amounts to a half a percentage point of China’s $13.6 trillion Gross Domestic Product, but the feedback loops are likely being felt on the production side of China’s economy as well.

That is undoubtedly great news for the Trump administration after 2018 had the largest trade in goods deficit with China in history at $415.9 billion, which led this author to speculate that perhaps the tariffs were not great enough to make a dent.

At the current pace, the trade in goods deficit in 2019 might come in at $375 billion or so, but that is with the first tranche of tariffs. We still have not measured the impact of the most recent tariffs, which could have an even greater impact that remains to be seen. Time will tell.

Taken together, this could be dealing a significant blow to the Chinese economy, which is dependent on exports to fuel growth. It is definitely slowing the economy down in China, which posted its slowest growth rate in close to 30 years in the second quarter of 2019.

Speaking to CNBC on Aug. 6, National Economic Council director Larry Kudlow cited the tariffs as the direct cause for the slowdown, saying, “the economic burden of these tariffs is falling almost 100 percent on China. So their economy, which has been deteriorating, you can look at any long chart of Chinese investment, retail sales and so forth, and you see a steady downdraft. Their GDP, which is probably inflated by several points, is coming in lower and lower. In other words, my point is with respect to our disagreements and with respect to the president’s tough negotiating with tariffs, I think China is getting hurt significantly much more than we are, as I said before.”

Kudlow added, “It’s just not the powerhouse it was 20 years ago, everybody knows that, and as I said before, supply chains are moving out, the demand for their goods is moving to other places, [and] a lot of people are coming back home.”

One potential headwind could the currency wars currently being waged, particularly with China’s new devaluation. The People’s Bank of China has attempted to compensate for the tariffs by devaluing the yuan against the dollar close to 5 percent since May, which earned it a currency manipulator designation from the U.S. Treasury for the first time since 1994. Time will tell if it is enough to offset the tariffs being imposed.

On Twitter, President Trump encouraged the Federal Reserve to weaken the dollar versus the yuan, euro and other currencies to keep the U.S. competitive globally, “As your President, one would think that I would be thrilled with our very strong dollar. I am not! The Fed’s high interest rate level, in comparison to other countries, is keeping the dollar high, making it more difficult for our great manufacturers like Caterpillar, Boeing, John Deere, our car companies, & others, to compete on a level playing field.”

Trump added, noting the current rate cut by the Fed, “With substantial Fed Cuts (there is no inflation) and no quantitative tightening, the dollar will make it possible for our companies to win against any competition. We have the greatest companies… in the world, there is nobody even close, but unfortunately the same cannot be said about our Federal Reserve. They have called it wrong at every step of the way, and we are still winning. Can you imagine what would happen if they actually called it right?”

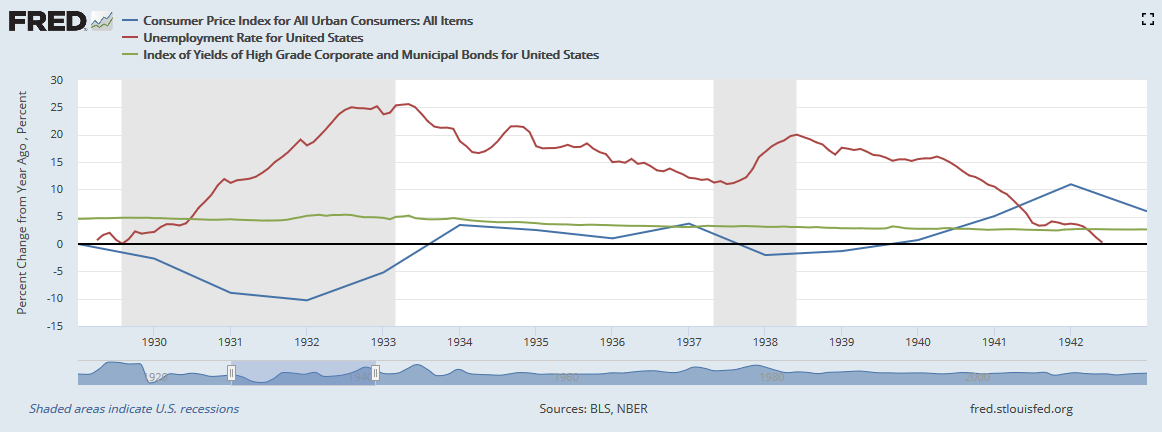

Here, Trump has a really good point. Competitive devaluations from overseas can increase that country’s exports, lower unemployment and give a boost to growth, and can have the opposite effect on trading partners like the U.S. where they export to. That puts the U.S. squarely in the crosshairs and could exert deflationary pressure on the economy here. Similar trends appeared to play out in the Great Depression and during the 2000s leading to the financial crisis, when overseas the ending of the gold standard and more recently China’s low peg coincided with sharp rises in U.S. unemployment and drops in prices.

Already, in June inflation only came in at 1.6 percent for the past 12 months, and so that is something the Fed should be keeping an eye on. As seen in the Great Depression, overseas devaluations can have a far greater impact than tariff policy in shifting the trade balance. Then, the U.S. attempted to compensate for declining import prices with the Smoot-Hawley tariff, but it was not until the U.S. came off the interwar gold standard in 1933 that deflation stopped and unemployment began dropping.

On monetary policy, the Fed and Treasury might need more firepower to counteract China’s foreign exchange market interventions and potentially devalue the dollar if necessary. Matt Phillips of the New York Times on Aug. 6 pointed to the Economic Stabilization Fund at the U.S. Treasury as an area with potential shortcoming: “The People’s Bank of China has the ability to print renminbi to weaken the currency if the exchange rate gets too high. On the flip side, Beijing has $3 trillion in reserves it can deploy to keep the currency from getting too weak. Right now, the United States doesn’t operate that way. It has some capacity to intervene in financial markets by using the Exchange Stabilization Fund, a vehicle under the control of the Treasury secretary, with about $100 billion of buying power.”

Phillips quoted Joseph Gagnon, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economic, suggesting, “Unless Congress gives Treasury authority to beef up the Exchange Stabilization Fund, it just doesn’t have enough firepower.”

I have encouraged the President and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin to consider proposals to bar China from U.S. treasuries markets if the currency manipulation continues to remove one of Beijing’s tools.

But for now, the President can take solace that the tariffs are having their intended effect of reducing the trade deficit with China — for now. If it hurts bad enough, it might be able to force China to the table, but the Fed has to get the dollar right and not let it get too strong versus foreign currencies or it could undermine everything the administration is hoping to achieve, and take the U.S. economy with it.

– – –

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.