by Katrina Trinko

It’s not fair.

This refrain—so quick to be invoked by young children, who seem to develop a thirst for justice very young indeed—may seem like a curious place to begin in defense of fairy tales. But let me explain.

But to backtrack a little further first—well, the latest salvo against fairy tales comes from two Hollywood actresses, Kristen Bell (“Frozen,” “The Good Place”) and Keira Knightley (“Pirates of the Caribbean,” roughly 10,000 period dramas).

"Don't you think that it's weird that the prince kisses Snow White without her permission?" – @IMKristenBell https://t.co/PaJySEzPry

— Parents (@parents) October 15, 2018

Bell told Parents magazine that when she watches fairy tale movies with her young daughters, she make remarks such as, “Don’t you think that it’s weird that the prince kisses Snow White without her permission? Because you cannot kiss someone if they’re sleeping!”

Knightley takes it one step further, telling talk show host Ellen DeGeneres she has banned her toddler daughter from watching films like “Little Mermaid” and “Cinderella.”

Why? Well, on “Cinderella”: “Because, you know, she waits around for a rich guy to rescue her. Don’t! Rescue yourself, obviously.” And on “Little Mermaid”: “The songs are great, but do not give your voice up for a man. Hello?!”

I’m reminded of journalist Salena Zito’s invocation to take President Donald Trump’s more colorful remarks seriously—but not literally.

Searching my own childhood memories, I’m hard-pressed to recall any sense of thinking that kissing sleeping people was great, waiting for a man to rescue me wise, or giving up my voice a valid life choice—despite my repeat viewings of these Disney films.

Just like I knew “Aladdin” wasn’t proof that I could hop on a carpet and fly or “101 Dalmations” a realistic take on the interior intellectual life of the high-strung Dalmation next door, I seem to recall that the worlds of Snow White and Ariel and Cinderella—worlds complete with half-people living underwater, dwarves in forests, and pumpkins molded into carriages—were hardly the stuff that provided practical rules of living for my gravity-bound, sadly unmagical world.

And yet these tales did provide valuable lessons.

It is tough to be a little child. Everything is new; you have no experience to fall back on. You are learning, being stretched constantly, and you are encountering—for the first time!—the bitter realities of the world.

You don’t have to possess an evil stepmother or wicked stepsisters—any selfish child on the playground who grabs your toy and isn’t caught will suffice—to understand that not everyone plays by the rules, or that the good are not always rewarded.

You don’t need to prick a spinning wheel or eat an apple to begin to awaken to the knowledge that you can be hurt by evil, and even engage in it. You don’t need to lose your voice to realize that forays into bigger, wider worlds beyond your parents’ arms and the comforting nooks of your home can shake you into a quiet stupor as you struggle to comprehend.

But maybe, as you toddle into preschool and watch Brittany tell the teacher she had the doll first and realize that the second serving of the candy your mom told you not to eat any more of gave you a stomachache—maybe you might need something else.

You might need to remember when all seemed lost, a fairy godmother whisked in and helped Cinderella. You might need to recall that Snow White was saved because she was loved, was rescued because someone else cared. And maybe as you eye Brittany, triumphantly playing with the doll you had grabbed right at the beginning of recess, you will remember how under the warmth and kindness of Belle, the Beast was able to become an OK guy.

As my mom told us: Life isn’t fair.

That’s one of those tough realities fairy tales grapple with, along with death and suffering. And then, too, there are beautiful realities whose mysteries they gently probe: the fact that love can change a person, that sometimes we’re helped unexpectedly, that our thirst for justice will be rewarded in the end.

These are not concepts that lend themselves to being told of, or probed, outside fiction. They must be experienced, not defined or explained.

After all, how does a child really learn what love is—by learning the dictionary definition or seeing the look on his mom’s face when he comes in the bedroom, terrified by a nightmare? But fairy tales, like the best stories, enlarge our world, take us to places and sentiments where perhaps our own relationships cannot yet bring us.

“It is the business of fiction to embody mystery through manners,” wrote American novelist Flannery O’Connor, and while that’s quite a burden to place on movies known for chattering mice and singing teapots, they manage to do so.

The world of fiction, particularly children’s fiction, is jammed with make-believe—Peter Pan flying; Harry Potter casting magic spells; Lucy, Edmund, Peter, and Susan entering a world through a wardrobe; and yes, Snow White and Sleeping Beauty being rescued with a kiss.

Often those flights of fancy—absurd when taken literally—enlarge our imagination so we can grasp something we could not comprehend, highlight to us a truth hidden among the humdrum of our own world.

At the end of the day, you can face down evil without a single spell; you can encounter the vividness of your life’s calling without creeping amid the discarded coats festering in a wardrobe.

And plus, as any toddler who’s tearfully presented a boo-boo to Mom knows, sometimes a kiss can save.

In our world—so focused on science and data, on math and the measurable—it’s easy to look only at the literal in fairy tales. But depriving our children of the beautiful mysteries they introduce would only ultimately impoverish us, and make us less human.

– – –

Katrina Trinko is managing editor of The Daily Signal and co-host of The Daily Signal podcast. She is also a member of USA Today’s Board of Contributors. Send an email to Katrina. Donate now.

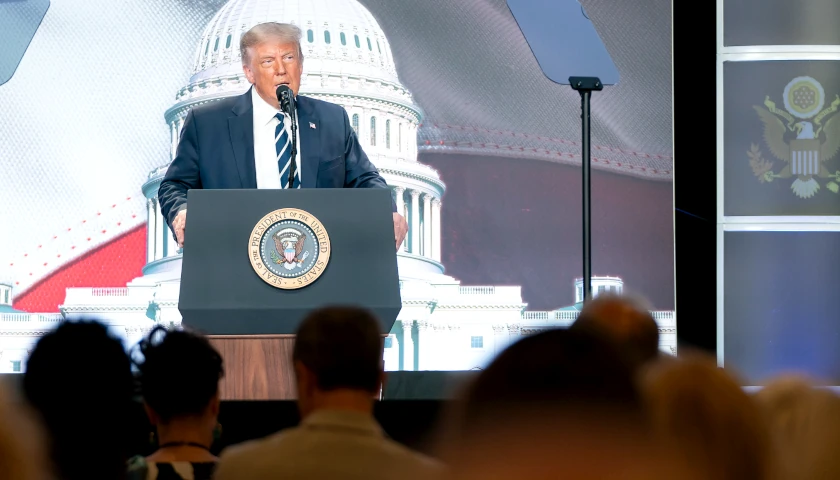

Image “The Sleeping Beauty” by John Collier, 1921.